![]() |

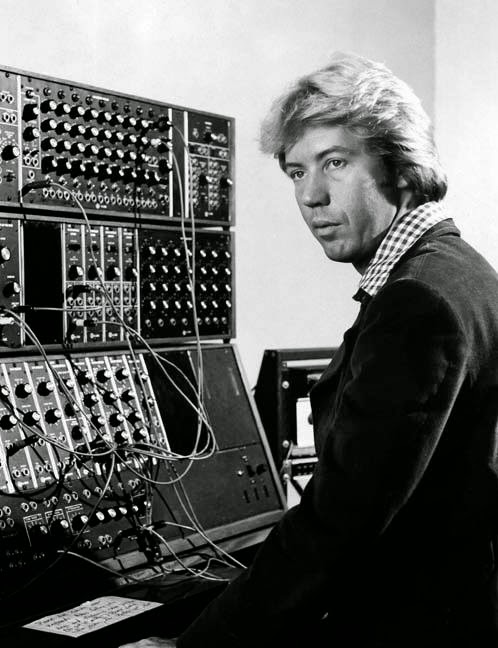

John Dinwiddie, with a Shure directional mike testing the Winters circuit, 1967.

Photo: David Freund, SOURCE Magazine, Issue 3. |

Think about a few years ago, and all things that changed in your life in a short period of time. Now think specifically about the improvements in human communication in the same period. Think about how easily it became to contact people all around the world, to find people with the same interests, on the same subjects, sharing the same cultural references, only geographically apart from each other. Of course the advent of the communication facilities, specifically via internet, brought very good things, and also bad things. But no one can deny that all the bad things that came along with the "modern days in communications" worth the price. It does for me, and it does for my research on electronic/experimental music and its pioneers and "eyewitnesses."

One of these days I was researching on the independent American magazine dedicated to the avant-garde music and arts "Source," and one name was recurrent in some texts, John Dinwiddie. I recognized the name, but didn't know where from. Then in less than two seconds, a light came to me - not a real light, only in my brain and thoughts... I hope so - and I finally got the answer: that was the same person that I had recently added as a friend on Facebook, who liked to comment on my posts, always with long stories. Long and good stories, I shall mention here. Not a single post of mine, specially on avant-garde music and composers, without a good story from John Dinwiddie. So, I decided it would be nice to interview the man someday, and went on and on thru the internet seas, but unfortunately I didn't find much more than a very good link to

an interview of John's to Charles Amirkhanian in 1973, via Other Minds' official website.I told John that I was willing to interview him, but wasn't able to find texts enough about him and, - not a surprise after my contact with him got further on, and I saw that the man, besides having a wide knowledge and a very good memory, has an enormous heart and patience to write long and good texts - I got a long text from him, a extended biography, to make my research and formulate the questions to the interview. And that was my main source to this interview that you can read below.

I'm very grateful to John Dinwiddie, who spent days and nights remembering his history, and writing that to send me, via email. Thank you so much, John! And thank you Gerda, John's wife, who not only encouraged the man to write, but also - I think so - must be responsible for part of this memories that John Dinwiddie share with us, here. And now, let's get into a long story, that worth every line!

![]() |

| John Dinwiddie and his wife Gerda, Germany, 2011. |

JOHN DINWIDDIE - Before I begin... definition, disclaimer, decafe

In having been honored, certainly considered more important than I am, to be included in Fabricio's research interviews, I am coming out of hiding at age 75 to revisit a world that I left 41 years ago immediately after John Adams conducted my last public piece, which he had also kindly commissioned, Lattices, a group of sequenced improvisational formats based on chromatic scales.

People who knew me may read my answers, some long, and wonder why so small a frog croak so loud. My life as a composer lasted 15 years and stopped abruptly when I was 34. I am indeed a small frog, and I don't think that anyone should be interested in me in that capacity; for 2/3 of that time I was a student composer, a low rank indeed. But I was a witness to events that I think were keys to the understanding of a complex time that was decadent as the term was used by Barzun, simply the delta land of a thousand plus year era. Some saw it as a new beginning, but the society decided in a ruthless and cowardly way that it was not to be such. Perhaps it contained its own seeds of destruction, and here I voice some of my thoughts on that part.

It is gone with the wind, leaving monastic composers to keep the faith much as monks kept literacy alive in the dark ages. We will have to save the world before we can hope for much more.

On with my little loud frog show and tell...

Have you given up music yet? Zen challenge.

Have you given up YOUR music yet? Pran Nath's challenge.

Starting with a story about Pandit Pran Nath.

It may have been 1973. I was shortly to abandon my strange odyssey as a composer which started more or less when I was 20 in 1960 in Luebeck, Germany. By now I had taken in what John Cage and David Tudor had taught me to so extreme a degree that I was all but convinced that whatever a composer was, I could no longer be one. But I was still searching, and I had very lately in the game taken LSD. That experience - and in 1972 may have been one of the last people in Berkeley to have had it - convinced me that I had experienced sound as a "living thing." I had also recently heard Pran Nath sing at Mills College in a presentation attended by a small group that included Henri Pousseur dressed to the 10s in a Tom Wolfe suit. Pran Nath sat on a prayer rug in the center of an attractive dormitory common room and chanted as if he were alone. His chanting seemed to make Pousseur nervous. He distractedly clawed at the door jamb next to him. It was what I expected, and it was completely over my head. I had heard that Pran Nath had once sung for four years straight a hymn to Krishna, stopping only for necessary natural functions. I already knew that Terry Riley and La Monte Young had left the American avant garde and were studying with him.

I was looking at the bulletin board in the UCB Student Union on Bancroft. There was a 3X5 card advertising singing lessons. The address was nearby in the Rockridge District of Oakland. The card had been posted by Pran Nath.

So I made the appointment and was ushered into a modest craftsman era bungalow on a pleasant street near the College of Arts and Crafts. I was greated by a human lion. He was cordial and to the point. Seated inside next to tambouras that they seemed to be tuning were to two lovely young western ladies.

We sat down and faced each other across a cocktail table. It was war from the start. I was in my early 30s, now a "certified contrapuntalist,"a past student of world famous musicians. I was not about to play the role of apprentice in search of a "master." But that is exactly what Pran Nath wanted from me, and he soon scolded me for what to him was arrogance. His scolding went something like this: "When I wanted to learn music, I followed my teacher around the town for days and days begging him to take me, and he finally did. But first he would push me away and push me away. And I kept coming back..."

I felt guilty and annoyed. The cultural gulf was too large from the start. But I wanted our interview to be happier than this. What could I say that could rescue the situation? I said this: "look, I have a problem. I think I have experienced sound and a living thing."

Pran Nath transformed instantly. He broke into a broad smile, enthused something like this: "Oh, yes!! Sound IS a living thing! It create the universe, it is baby's cry, everything that is not corrupt is song! I will take you as a student, but I warn you that if you follow me you will have to leave all that you think you know about music behind you."

I knew that I could not do that and told him so with some regret, with a real sense that the path of music went much further than I was willing to go. I had discovered a limit, wondered what lay beyond, knowing that the price of admission too high for me. He appreciated my honesty. We parted friends.

I learned then or later that the two girls were not tuning their instruments to some standard as do western instruments. They were tuning the instruments to themselves.

Now how am I going to answer these questions?

I will try to let the person speak who was there, and more than a little of what I say may strike a reader as naïve, but that was the camera lens that took the pictures, me from age 20 to 34.

Life in our society is an opera. Or a musical. Or a chain gang singing. Circumstance and choice determine the music, and our lives are the plots, but there is a music track somewhere much of the time, for some all of the time. We rue the fact that it is in public places wether we like it or not, that a lot of what we hear amounts to crowd control. And there is never silence. Of course nature isn't silence, but I am talking about the price in noise that we pay for civilization. High in the wilderness, an occasional helicopter will disturb. The Sierra Nevada's spectacular Desolation Valley is directly under a commercial airlines flight path to San Francisco.

Recent media dazes into some zombie cakewalk our gear drenched youth. It isolates them and deposits them into a virtual world, a pernicious cocoon. Science fiction writers in the mid 20th century wrote about this. Now it is no longer science fiction. I looked yesterday at high definition TV at Best Buy. Thank God I can't afford such gear. I might otherwise never go outside again. Now we watch gorgeous shots of nature inside that will soon be outside. Is our future to be like that engineered death scene in Soylent Green? Do we see flowers soon that are not outside at all? And imbedded in this crisis, am I to speculate on the future of new music here? I'll certainly try to do that, but...

This is now a century old story at least. Music was not needed with innovation of talkie movies. But the band played on and still does.

If asked how originally bonded to music, Fabricio's first questions to me here, I am really being asked to analyze social roots of my own opera, and such roots vary endlessly. Robert Ashley once told a group of us that after he played his M. A. piano recital, he quit and went on to now world famous other things. He came to recognize that in his childhood he had bonded to boogie woogie and blues. He did not have European classical music in his DNA.

I did, I am not a snob who considers that bonding a virtue. It is fate, nothing else. Classical music is also class music, and in our society its pretentious have been divisive, in the end self destructive, since classical music has now hit a log jam of established repertory which throttles innovation. It is now what Larry Austin called it 50 years ago, a museum culture. It is the opera of the rich and its imitators in the middle class. Veblen corrosively analyzed that pairing almost a century ago. I do not burn incense at the altar of classical music. I don't much like the bourgeois culture that is bundled with it. But it is what I bonded to first, so its spirit is the core of my musical experience. That informs everything that I now write, especially so the first quite long answer.

Now to Fabricio's e-mail interview questions.

![]() |

| "John Cage preparing to take his turn in a 15 hour performance of Satie's Vexations that bracketed his multi concert environment MEWANTEMOOSEICDAY at U.C. Davis in 1969. He asked me to repost on the day, and that report, which may be found with the name as the title of that report in SOURCE, Issue No. 7, and in the recent U.C. Press anthology of Source edited by Larry Austin and Douglas Kahn, photo by Richard Friedman." John Dinwiddie. |

ASTRONAUTA - Hi John Dinwiddie! To start from the beginning, what was the relationship with music and arts in your home, when you was a child? And which memories do you have about the earliest times that music and arts began to be interesting for you? Which musical instrument first caught your attention, and what did you like to listen (and play) at home in your childhood and teenage days?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - I was born into a soon to decline Berkeley California upper middle class family in 1940. We lived in a home on Stonewall Road in the Berkeley Hills behind the Claremont Hotel that was designed by my father, a fast rising Bay Area architect, John Ekin Dinwiddie, once a student of Eliel Saarinen, who had been the Dean of Architecture at Tulane for 8 years when he died at age 57 in 1959.

Immediately after WWII he was briefly the first American partner with Nazi refugee Eric Mendelsohn, who designed the famous Einstein Tower in Postdam. Mendelsohn warmed to his example and reinvented himself in his last years as a fine practitioner of the informal Japanse influenced 2nd Bay Area style.

Dad's mother, whom we called "Garma," was the financial power in the family, the widow of the founder of the Dinwiddie Construction Company which lately has built the new Getty Museum and was for a half century a leading construction company in San Francisco. It built the Transamerica Tower and the world headquarters of the Bank of America. Garma was herself the niece of Colonel William Starrett, who supervised the construction of the Empire State Building.

Grandfather Bill Dinwiddie was a high school educated contractor who had migrated from Chicago first to Portland, then to San Francisco shortly after the end of WWI. He was working class in his outlook, was known to sign large contracts with a handshake. Never forgetting this, he never laid off anyone during the depression, and it is said that the line at his funeral was two blocks long, mainly his employees and their families.

He had to his credit the Russ Building in San Francisco, which remained the highest building in San Francisco until long after WWII. He built much of the Treasure Island, and the Zeppelin hangar at Moffett Field. He died in 1932, sold controlling interest to his partner. Otherwise I might have grown up rich.

Bill and Garma had five sons, my father the middle, and they all were given Steinway B grand pianos for wedding presents. Ours was the best, even signed by Alfred Cortot, who had once used it for a local recital. It belongs to my older sister Bettie, a retired piano teacher in Tacoma, Washington.

Bettie was 7 when I was born, only a notch or two less than a prodigy. That Steinway was her piano. She became a favorite student of Marcus Gordon, one of the best teachers in the region. She was playing advanced works by Chopin and Brahms at age 10. And age 10 was 1943, when I was 3 years old, and when our parents divorced. That year was as terrible as any in WWII. It started with the surrender of Germany at Stalingrad, continued with the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, Guadalcanal, the destruction of Hamburg. The allies invaded Sicily. While Mussolini regrouped in northern Italy, Rome declared war on Germany. The time line this year was a nightmare. Our family tragedy swam with the rumors of the terrified fish of the world. But unless a family member had become as casualty, all was rumor unless it was news. "There's good news tonight," intoned conservative radio commentator Gabriel Heatter every evening at 6 P.M. In 1943 it seldom was.

By that year the Bay Area had been half sacred to death. Until Guadalcanal, the war in the Pacific had not gone well for the U.S.A. There had been blackouts continuously since Pearl Harbor. And although there was less censorship in the media than one might have expected, the first days after Pearl Harbor were filled with paranoia fueled by disinformation. After all, California was the next landfall after Hawaii and in fact it was attacked, if insignificantly, by a submarine whose deck gun hit an oil storage tank. And nobody knew what might come next.

The bluffs around the Golden Gate bristled with cannon and antiaircraft guns in a labyrinth of hardened pill boxes. Troops were continually getting on and off the Key System trains that crossed the Bay Bridge and stopped for at Yerba Buena Island where Chester Nimitz had his home, that island connected to Treasure Island. The Presidio was lit up every night unless there was a blackout. The Cyclotron above the University of California exuded sinister mystery; the forested area nearby was fenced off. Few knew anything about what was going on up there, but everyone suspected that a secret weapon was in the works.

One of my father's clients was commandant of Treasure Island, and when he, Captain Harris, received the news of Pearl Harbor, he already knew two disturbing, highly classified facts. The first was that there was a second Japanese carrier division unaccounted for. It could have been close to California. He also knew that in California were only 8 serviceable and armed intercept fighters. Captain Harris had built a bomb shelter a year before in Tilden Park for his wife. When the news of the attack arrived, he first deposited his wife into that shelter, then drove to work.

All of this spun about in the emotions of the adults as I came into full consciousness and of course affected me. I was variously fascinated, bewildered, scared. I was smart enough, remember to this day most of it very clearly. I certainly remember the blackouts. Mother would hide Life Magazine from us. We always found it, saw the war through the eyes of Life's great photographers. But we never once saw the war itself.

So there I would sit in the midst this energy, under Bettie's piano, the best seat in the house, listening. My mother's growing unhappiness was reflected in the records she played. Sibelius's Waltz Triste, again and again. Such became our incidental music to the stressed events of every day. A lot of it was sad, and a lot of it was dramatic. Rachmaninov's 2nd Piano Concerto ruled. Addinsell's Warsaw Concerto would soon become the Readers' Digest version of the same.

We played Strauss and Lehar waltzes. The Merry Widow chased away that poor dying dancer whose music destroyed audiences 50 years later in the Fantasia send up, Allegro ma non Troppo.

Our view of the S.F. Bay Area was panoramic and stunning, the center line between both bridges. Our steep one hairpin turn street was recently developed and was lined with first rate residential architecture, beaux artes, craftsman, modern. I was Heaven with its floorboards about to falling out. Bettie's music, the music from the phonograph, my father's amateur violin playing, Garma's own playing of the same 6 pieces over and over was what painted onto my ears its prevailing mood. And the wind in the lethally fire prone Eucalyptus that silhouetted in the moonlight were alien magic. Garma would play for Musical Chairs at birthdays. Country Gardens. The easy part of Chopin's The 3rd etude. The 2nd movement of Beethoven's Opus 13. Down the street the next Garma might be doing the same thing. Much revolved around the Berkeley Piano Club, still in existence today. She was one of its founding members.

The divorce ejected us from this minor Palantine Hill but landed us directly under it thanks to Garma, who bought us a house above College Avenue in the Elmwood District. It too was architecturally interesting. Its stairwell was canted out from the front wall like a two story lantern. Neighbors called it the pregnant house. Now we looked four blocks up to the Claremont Hotel instead on two blocks down.

The Elmwood District looked down home American, with a shopping district right out of Norman Rockwell. But it was still far from the bottom of Berkeley where raw sewage was still pumped into the bay, leaving a vile odor. For miles along the highway to the Bay Bridge that odor forced shut all car windows. The 76 Oil Refinery near the Carquinez Bridge at the other end of the East Bay also exuded an odor that certainly delivered chronic illness to the working class families living nearby. The East Bay had its well heeled neighborhoods, but as a whole, the Bay Area was on wartime footing and broken in many serious ways, the East Bay waterfront the worst.

And there was this stench, the emptying of South Berkeley's when the Americans of Japanese descent were interned in concentration camps. The evacuated properties were then filled by largely Afro-American workers from the south who built the Liberty ships.

I only saw this part of Berkeley from the windows of the Key System train, but right from the start I noted the decline in housing as that train moved down until at the last stop before the Bay Bridge at the flop house Key Hotel, one saw real mean streets.

All told, there was a smug and cozy conformity to our neighborhood. It was "above the tracks," red lined. Many households employed "colored ladies," who helped in housecleaning once a week. I winced 20 years ago when at a Berkeley City Council meeting I heard a Berkeley Hills matron use this expression. Berkeley was liberal except where it wasn't.

Musical tastes were pretty much standardized, the bourgeois upper middle class canon. Every other home had an upright piano, usually with a dog eared copy of "Music the Whole World Plays" on the music stand. Open it and find Anton Rubinstein's "Kamennoi Ostrow." Nobody could play it. Every fifth house had a grand piano, and in every one of those with children, some kid was taking piano lessons whether liking it or not. Average piano teachers were well off, good ones rich.

Record collections were all pretty much the same. Classical music was dominated by RCA and Columbia. The Franck Violin and Piano Sonata was very popular. Popular music was also standard, Bing Crosby, Andrews Sisters, Sinatra, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and a dozens more. Ima Sumac and Dorothy Shay were hit novelty singers, one exotic, the other satirical. Cartoonist George McManus satirized the taste of the wealthy in Bringing Up Father. Maggie was forever dragging Jiggs off to the opera or herself singing off key while her permanently drunk brother sprawled in improbable postures on an ornate, curved staircase.

And an endless parade of radio dramas stole from classical music. The Lone Ranger sewed together Rossini and Liszt. The Green Hornet used The Firebird.

The FBI in Peace and War used the march from the Love of Three Oranges...

I wanted more. I wanted it stranger. The anonymous there music to The Mysterious Traveler haunted me. If it was weird, I listened. I heard a modern orchestra work on the radio when I was five, ran down the stairs in glee shouting, "MOMMY, come hear, the ORCHESTRA'S DRUNK!!" The war and the divorce, Bettie's role, left me as an afterthought, "nice little Johnnikins under the piano." The neglect left my id dangerously intact, and this need to tear down the conventional now may have been an unconscious accommodation to the chaos that came with a recently broken family.

I found a lot of popular music boring, and I made up classical music in my head up on Stonewall until the divorce. Then I stopped. I remember being able to catch myself when I allowed my imaginary music to slip into some banal sequence of diminished 7ths, stop myself in annoyance, increase my concentration. I was composing, and I knew it. I also knew that I equated predictability with quality, the less predictable the better.

And there was this. My maternal uncle was a Captain in the OSS. Prior to WWII, he was a freshman lawyer in San Francisco who early on picked up a very rich client, Ralph "Bogey Man" Reynolds, a leading endocrinologist. He and his wife had built at Soda Springs near Donner Summit a fabulous ski lodge with double bunk rooms for the guests, a roaring all around stone fireplace, the whole faux Tyrolean works. Swimming pool. Tennis court. This was not just some cabin. The reynolds had us up often, and I know that one reason was sympathy for my mother's situation. She had been astonishingly brave; the divorce was not her idea. But anyone in her situation could have used sanctuary. For me it was Heaven above Heaven.

Gas rationing often compelled us to take the train. Once we went up just after the colossal ammunition ship explosion on July 17th at Port Chicago. It killed 320 people, and the shock wave imploded nearby box cars. Not one but two side by side and loaded ammunition ships blew up, raining debris for miles to Martinez and beyond. I remember our train crossing a trestle not far from John Muir's home near Martinez. In the tracks next to our window passed by a hole in the ties that had splintered a half dozen of them. Most probably, something had fallen out of the sky from that explosion. Repairs took months.

Of course this was to me more exciting than scary. Kids love train wrecks until they are in one. Same with war, a delusional affliction of children in th U. S. A. during WWII as long as no family member became casualty. My wife, born in Luebeck, Germany in 1941, only to suffer the first carpet bombing attack history 5 months later, has a different story to tell about her childhood.

At Soda Springs, my sister and I would go down to the railroad platform. Soon a big train was bound to come, from east of from west. Big meant the typical freight train carrying was materials from Chicago to Port Chicago, Vellejo, and Treasure island. These were the giant cab forward, oil tendered locomotives unique to the Overland S.P. route. The reason these engines were built cab forward was that between Truckee and Donner Summit they had a pass through miles of snow sheds which funneled the smoke into the cabs. This solution saved lungs and lives.

At 4 I less than half the height of the flywheels on these behemoths. They would come up with three engines in front, two of them slaved. The engineers would always wave. Then the payload would be one hundred cars at least. Box cars, tanker cars, and flat cars, those often carying canvas enshrouded antiaircraft guns or howitzers, each can with an armed guard, a thought provoking sight for anyone, let alone a little boy.

Then came two pusher engines and tenders, finally as many as six cabooses for the staff. At the height of WWII, these would come by at a frequency of one every two hours or less.

They also came at night. I would lie in my bunk room upper berth while the adults were still downstairs with their cocktail and chatter, and listen. The Sierra Nevada is on the west side a series of east west canyons that go for almost 50 miles to the 500 mile long escarpment that drops in less than ten miles as much as 5,000 feet. This wedge geometry accelerates the wind from the Pacific and the Central Valley. During blizzards, winds can reach hurricane force at Donner Summit. Read "Storm" by George Stewart for a convincing description of the havoc of such storms. That wind though usually gentle, is almost always there at some time during the day or night, and in the far distance, a train sounds like the wind except for its puffing, itself muffled and indistinct at first. When a train comes from the east and shoots out of the snow sheds at Norden, three miles east of Soda Springs, one hears it instantly and very soon after it passes a quarter miles away from the Reynolds lodge. There would be as many as meters of puffing as there were engines, and they were not synched, even if they were close together in frequency of the puffs. The multiple puffing was arrhythmic, and then there was the Doppler effect.

From the west, who knows how far away was a train when first heard. And as soon as muffled puffing was distinguishable from the wind, it might suddenly go silent as the train entered a tunnel or snaked behind any kind of natural sound barrier. But soon it would appear again, often much louder and suddenly. Now one could follow echoes. It would disappear into the wind, become a ghost of itself, tease, fade, roar back. I would listen to this natural counterpoint for maybe 20 minutes before finally the full force of the sound burst upon Soda Springs, passed with the click of the cars quite audible, then the final majestic, misaligned puff of the two pusher engines, finally all into the snow sheds, leaving the Sugar Bowl and Soda Springs to the wind, which always has the last word.

Downstairs the phonograph might be playng in the evening Strauss waltzes or the Grieg concerto. I first heard that piece there, and once I listened to it, I looked down onto a table where there was a Life Magazine open to a picture of Norwegian prisoners being marched off by German soldiers. They had their fingers laced over their heads, the preferred Wehsmacht posture of obedience.

I am telling all of this to sum up what people have wondered about me. How could I have such conventional and radical musical tastes at the same time? I doubt that to be really too unsung for anyone who has been in the trenches of the avant garde. John Cage once told me that a childhood ambition of his was to become a pianist specialized in the music of Grieg. And he loved indistrial sounds as we all know. My season in avant garde music was surely driven by my memory. I had heard one of the greatest mixes of natural and man made sound in all of human history. Steam locomotives of this size disappeared shortly after the war, the new diesels cost less to operate and were lower maintanance. There is one perfectly preserved cab forward locomotive at the Sacramento Rail Road Museum. Five years ago with my grandson, I stood next to it. I still felt small.

ASTRONAUTA - When did you discover and become interested in avant-garde music for the first time?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - It must have started with the trains and the mountain winds, maybe the ocean which also was not far from us. I loved white noise of any sort, pink, purple, blue. I do know that. Nothing in new music was going to take me home again, but memories were always under the floorboards.

That, and the restlessness of my ear. I was frustrated by the limits of traditional composition. Great music is a train ride to the unknown. When the tracks are too well learned, trouble. One searches for a new railroad.

But my odyssey was long. I remember still when Bartok seemed dissonant to me in a way that irritated me. I knew somehow that I had to overcome that irritation, that somethings very powerful was in front of me. What was the first new music that I tried to learn? Pieces in Bartok's For Children.

I always pushed through my resistance, like getting used to spicy food. I saw Fantasia seven times. Stravinsky, Mussorgsky, and Dukas stood out, the last's eerie augmented fifths chords in the introduction. I didn't know what they were called, but everybody responds to the four triad types. We all know music long before we learn it.

![]() |

Cathedral Rock reflected at Red Rock Crossing, photo

by John Dinwiddie, 2005. |

I went to an unusual progressive prep school when I was 13, the Verde Valley School near Sedona. Arizona. Sedona was a one horse town in those days, a broken down western movie set nearby, a lapidary store run by a charming old huckster in a Navajo slide tie with a turquoise in its cast silver setting. He was also the world's leading scholar on meteors. Next door was the Hitching Post Restaurant, now hidden in a labyrinth of curio shops stuffed with kitsch. On the roadside for sale ten years ago two story high chrome plated horses. Charlatans with wire pyramids for hats competed to escort gullible tourists to "power spots" near Cathedral Rock. A fleet of strawberry colored jeeps hauled tourists up Schnebly Hill where car ads are now often made. Now Sedona is the Carmel of Arizona. Many of us who were there in the 50s now refuse to go back, do not want memories disturbed. I did in 2005. My memory survived, and it left me with plenty to complain and laugh about. Back then it was real, peopled with old Navajo ranch hands in jeans and weathered faces that hinted that they grew out of the desert dust. One could drive though Sedona barely having noticed it were it not for its setting. The area would have been one of our greatest national parks.

The road south to Bell Rock was paved, but at the crest where it passed just to the right was a cattle guard, beyond as far as it went, spine jarring washboard. Where now Oak Creek Village sport a four way signal, the road turned right to Verde Valley School road. Now there was no washboard, just red sandstone strata, ruts, and razor sharp sand stone dust. A car on this road could be seen for miles because of the dust cloud behind it.

At this corner, where now there is a shopping center, suburban housing, and a golf course irrigated from God knows where, there was at the southern corner an abandoned white one room school house. Other than the valley and the now famous giant rock formations, there was only that, one white dot in a Martian landscape greened with sage brush and scrub pine. That school house had been used by Colonel Brady, a pioneer in Arizona education. He was now on the Board of Directors of VVS along with Clyde Kluckhohn, John Collier, and George Boyce. When in a school bus without shock absorbers I first took this road, I was driving through history that I had yet to learn. I did know that it was the wild west. So did Hollywood. Several westerns had already been filmed in the area, and two more were to be filmed while I was there, Johnny Guitar and Broken Lance.

The co-ed Verde Valley School was 5 years old in 1953, with a student body of 120 and a student-faculty ratio of 1 to 10. VVS had a huge record library in its music building, and I wasted no time exploring it. In it was the complete works of Varèse, of Webern as well. I first heard Bartok's Sonata for 2 Pianos and Percussion, Ravel's piano concerto and the Capriccio of Stravinsky, both of them revelations, as was Varèse's Ionisation. And Martinu's Sinfonietta Giacosa. Martinu never topped it.

So one might say that I discovered avant garde music in 1953 at VVS. But classical music also grew on me, and my first hearing of the D minor Piano Concerto by Brahms was decisive. I did not yet know Beethoven's 9th, so I did not know the reference, but I did know that the piano entrance was an extraordinary departure from any piano entrance to a concerto that I had ever heard. Its return to the volcanic trills of the opening was magnificent and elegant. The second movement I decided was the greatest single composition I had ever heard in my life. I still consider it one of the supreme works of the 19th century. That changed me. Steve Soomil, who went on to become a student of Milhaud at Mills College, wrote in my yearbook, "to Brahms's greatest fan."

Music at VVS was everywhere. We had annual three week long anthropological field trips deep into Mexico, a similar one week trip in the fall onto the Navajo and Hopi reservations. In both cases students were deposited in small groups at one place or another, sometimes just one student, perhaps at some remote school or Navajo shepherd's Hogan, left there, to be picked up at the end of the trip. Spanish was a requirement. 10% of the students played guitars and sang folk songs in English and Spanish. The rest of us joined in. We all sang. Our Spanish teacher who had grown up during the Spanish Civil War made up songs for us, many ridiculous. We had work jobs to justify a fair tuition with many scholarships. We built our own school. So Mara would give us a work song: "Vamos todos depresita a trabajar, holgazones no podemos soportar." We wasted no time making adjustments. "Vamos todos depresita a chingar..." She would start each class, "Viva España! Abajo Franco." Because in those days Franco was still not at all "abajo."

We were taught extreme self sufficiency. One night on the Mexico Trip, in the middle of nowhere, the school bus headlights failed. Ham Warren, the intrepid founder of the school commanded us, "just fix it." Phil Dempster, a science whiz, did just that, and our caravan continued.

Two more tales, about events on the Navajo trip:

The first happened when I was a freshman. Hamilton Warren was rich, and the school had been established with his family money. He was also very tough and on the ground if a bit reserved with the students. On the Navajo Trip Ham as always drove the old school bus, the most unpredictable and largest vehicle in the VVS caravan. He was taking us up Navajo Mountain to a Yeibichai.

The road was steep, narrow, unpaved, rutted, precipitous drops here and there. We drove the whole trip in 2nd gear. We arrived after midnight, tumbled out half asleep and looked upon the scene. We were on a large plateau about 3/4 the way up the mountain. What we saw was a huge circle of people, at least 100, who were doing a static two step around a bon fire twelve feet high that sent sparks and smoke far above the crowd. Dust from the dancing ringed the smoke like an upside down atomic bomb. The scene was sepia, all earth tones, beyond the intense yellow light of the fire, every dancer in dusty tan attire, couples all the way around the circle, singles interspersed. It was informal. people would join in, drop out, come back. It had been going on since sundown, and it would go on until dawn.

And in step with their static sted they chanted incessantly, "hey ya, hey ya..."

I looked at it, and I wondered why Ham had taken all the risks to drag us up a dangerous montain road just to see this rather boring scene. But I also answered the question with another: "what was I missing?" I knew that what I saw was utterly alien to my experience but not to the Navajo. To them the proceedings were sacred ritual. So what might that have been? This was my initiation to tantra and mantra. That prepared me for Pran Nath.

The following year the group that I was with went to stay for a week at the Rocky Mountain indian School near Brigham City, Utah. This was a Dept. of Indian Affairs vocational boarding school. George Boyce, on our Board of Directors, was director here.

It was as long a haul for the Navajo Trip as any made. It was a bitter November, and I was to get a bad case of the flu that approached pneumonia before it was over, but I was young and recovered quickly enough. Each caravan truck required always a "shotgun" companion in the cab to guard against the risk of a driver falling asleep. One night I had that duty, and the radio was on. Suddenly we heard this eerie baritone voice...

"I keep a close watch on this heart of mine, I'll walk the line."

We heard Johnny Cash as he first happened. As with the Brahms, I knew that I would never forget it, and out there, on that lonely highway, snow falling...

At Rocky Mountain School, too many stories compete, but only one about music. navajo chant has a default two note refrain, "Hey ya, hey ya..." one hearts it in the Yebichai not as refrain but as mantra.

Also everywhere on the radio, on jukeboxes, the music was American pop music. No "hey ya." So one day we were in the school canteen buying soda pop when on kid started songing "Do not forsake me oh darling... hey ya hey ya..."

I was later to learn that music notation may have started in response to the inability of Rome to control the liturgy in its new trans Alpine acquisitions. The Frankish tribes would do their pagan version of this troping. "Kyrie Eleison... hey ya" (their counterpart.)

VVS never ran a tourist operation for rich kids, even if a few of them were. it was up to date on the most enlightened anthropological concerns, and Ruth Benedict's Culture in Crisis was on everyone's reading list, about the threats to the Hopi culture.

The kind of troping that we hears in this canteen reflected just that threat. In Black Canyon under the Hopi reservation, we once saw at a government outpost a huge sign next to the highway that said, "TRADITION IS THE ENEMY OF PROGRESS." And the theme of Oliver LaFarge's Laughing Boy, also on our reading list, was that the product of severe sulture clash is death. Preparing students to assist in this crisis was the second mission of the Verde Valley School. And I was learning now that music was a canary in the mine shaft that reported on the progress of this issue.

There was in fact no school like VVS anywhere in the U. S. A.

I taught myself how to read music, was forever in the practice rooms trying to play Brahms and Rachmaninov. The musicteacher the following year had very advanced students to attend to, so I was on my own. I improvised a lot, just wild linear chromatic stuff with no particular system at all. My hands led and my ear followed. I learned that generic gestures could tell stories, that the precise pitch work of disciplined common practice improvisation was not only the way to skin a cat. On this too I was defaulting into unknown sonic territory. How did I know that I probably sounded like bad Roger Sessions? Duting my sophomore year I attempted an atonal string quartet, did not get far, but I remember it. It was better than I thought at the time. I was not a good steward of whatever gift I had, found no encouragement either at home or at VVS. Several of the more talented and advanced students however did challenge me, and one helped my, taught me more about jazz that I had yet learned. That was the late Ethan Crosby, older brother of David Crosby. He introduced me to Marry Lou Wolliams, Gerry Mulligan, many others. His tragic end in 1997 was terrible news for all who knew him.

Two student were step sons of Ferde Grofe, Grofe once gave a bunch of us an impromptu lecture-demonstration. Gorfe was a jolly fat man. He sat down at Ham Warren's piano and let fly with his Grand Canyon Suite, screwing it up in no time. He laughed, Snorted, "Well, composers make lousy pianists." Then he got right back to work. It was a lesson in attitude. If he could screw up and live, so could we.

Tulane and on...

I went to Tulane on a service scholarship, because my father was the Dean of Architecture. All the pieces that those advanced kids played at VVS continued to taunt me. I did love all of them. But I wanted some proof also that I too actually stood on this planet. So far, i had a famous father, a gifted sister, and no identity of my own.

A fine Brazilian pianist, Egydio de Castro e Silva, took me as a student. He had been a student of Robert Casadesus, and he once knew Bartok. Istvan Nadas, who knew Bartok better, was next door at Loyola, was soon to join the faculty at Stanford. in the next year I learned many of the pieces that those more advanced students at VVS were playing, Mozart's C monir Fantasy, Bartok's Suite, Opus 14, several character pieces by Brahms, the Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue of Bach, and the Cat's Fugue of Scarlatti. All but the Bach I played before a faculty jury since I took piano for credit. I acted and worked on sets in the Tulane Drama Department, when the Tulane Drama Review was still there before mass exodus to NYU. In the second year I was fool enough to major in architecture, and my father was distracted enough to let me do it. At the end of that year I was told by the professors that I had them completely bamboozled, that they had no idea whether or not I had the goods to become an architect. They did opine that I should get out of Tulane.

That was 1959. I skedaddled. I was now vulnerable for the draft, had no idea what I really wanted to do, so I enlisted in the USASA, which added a year to my service but all but guaranteed that I would be sent to Europe.

Before I left for basic training, Harpo and Chico Marx had come to town to chase each other around a piano in the Jung Hotel on Canal Street. I went with a date, and we sat right next to the railing that looked down 3 feet to the performance floor. So these old trolls whose skins were as weathered as those cowboys in old Sedona, did their famous act. Behind us a woman alone at the next table was clearly drunk. She would periodically call out, "Harpo, Harpo, play One Alone. PLEASE play One Alone!" Loud, whiney voice. It did get to them, and we watched their irritation mounting.

After about the fourth call, Harpo and Chico stopped directly in front of us. I could have reached out and touched them. Harpo whispered to Chico, "What the hell is One Alone?"

After the show we talked with them for a few minutes. They were kind and patient. They were also tired, brave old men keeping things going.

I went through basic at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina. "Yo gon get up at five a goddam clock in da mornin," drawled a black drill sergeant the first night. I thought, "he just put 'goddam' between 'o' and clock'." This is trouble. It was also music. I was about to learn a whole lot of music that I had never known was music. "I don know but I've been told, Eskimo pussy's mighty cold." That music. The Army had been integrated ever since shortly after the end of WWII. Ft. Jackson was near Columbia, South Carolina, a notorious hotbed os racist rednecks. We were not allowed to go to town, too dangerous. Although the ASA was an elite of the military, basic training was for everyone who could sign his name. There were recruits from the Ozarks who had never had a pair os shows. Those who had musical chops REALLY had musical chops. There was no room for bull shit. Beer cans were a foot long. i had to put on boxing gloves in a dispute, still have a small scar on an eyelid as a memory. The executive officer stopped the fight when he thought that the honor of the litigants was secure. I was lucky that he did.

Army bases surprisingly to me had fine libraries with large record collections and listening rooms. So during off time at Ft. Jackson I was able to continue exploring Bartok and others. The same held at Ft. Devens, Massachusetts, my next stop. I finally wound up in March, 1960, in Luebeck, Germany, the home town of Buxtehude and Hugo Distler, where at the time Christoph von Dohnanyi was local orchestra conductor and Walter Kraft was organist of the Marienkirche. he had recorded the complete organ works of bach and Buxtehude for Columbia.

It was here that I decided to become a composer. At 20 years of age, that decision was just plain nuts. But in Germany, composition is considered a craft that does not require genius. It ranks perhaps as a learned vocation which has a middle class that makes a living, often as church musicians. In Germany, the Hanseatic era had spread hundreds of sturdy little brick Gothic churches all over the countries around the Baltic, while the Holy Roman Empire had done as much in Bavaria and the south. Around Luebeck one finds them today every 10 kilometers or so. Almost every small town old enough has one.

The local conservatory was at time called the Schleswig Holstein Musikakademie und Norddeutsche Orgel Schule. The second part was presided over by Walter Kraft himself, Kapellmeister of Buxtehude's Marienkirche where J. S. bach once apprenticed. It is the largest brick Gothic structure in Europe. His half of the academy trained "Dorfkirche Kapellmeister." And now as then, there are far more little churches about than musical geniuses to work in them. What my own gift if any promised would find its way, but here at least I had room to be a journeyman. I just wanted to get inside the door.

One night we attended a performance of Abraxas, by Werner Egk. After a perhaps promising start, the piece as far as I was concerned lost it, and here it was playing to a full house. I thought, "I can at least do better than that."

And so off I went.

ASTRONAUTA - Your father was an architect, and you also studied architecture. How do you relate your studies in architecture to your studies in music?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - I was only an architect major for one, star crossed year stuffed with outrageous tales that have no business here. First year architecture was before computed aided design tools traditionally brutal and very boring, a ton of busy work, drudgery. My class had 40 students in it, and the next class above had about a dozen. That said a lot about the true purpose of first year architecture.

But I had innate instinct for a proportion and my tasted and standards were forbidding to a fault. I was to become a kind of avant garde music fanatic at my worst. Here I was a modern architecture, art, literature probably necktie fanatic. I was that, come to think of it. San Francisco, which I still visited in summertime, was under the spell of the Beat culture, with it Zen. Ernst Neckties on California Street were the best looking ties on earth, narrow, earth toned patterns, excellent fabric, each small batch. Snd not really too expensive. I wore nothing but Ernst ties. Tweed jacket with patched elbows, jeand, half Ivy League, half west coast. That was the costume of preppies in those days, tie optional however, call that one formal dress. Or the black turtle sweater and Beret, copy of Howl in every back pocket. This Apollonian taste was to my liking. What was about to come much less so. I felt hippies to be invaders.

My tastes were most of all forged in the shadow of my father, a splendid architect who never strayed from the command, "form follows function." VVS continued that foundation with an art teacher, John Sandlin, a dynamite painter, who taught the history of art with unforgiving vengeance. Like many prep school teachers, he would have rather taught college, so he did just that until an uptight dean on academics gave Wylie Sypher's Four Stages of Renaissance Style the Fogg Test. The Fogg test counts syllables per word on a sample page and then rates a book as to its appropriates for grade levels. That book rang the bell at the university graduate level. The dean tried then to pull it, and, naturally, the school erupted. We had already learned enough there to be uncontrollable when things got silly.

Sandlin's Reading list also included works by Sir Herbert Read, (just about everything) Grace, Eliel Saarinen (The Search for Form, The City), Lewis Mumford (just about everything), Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan - you get the idea. He stuffed the school library with Skira art books until the librarian said that she could not afford to buy any more.

And Geoffrey Bret Harte, grandson of Gold Rush story teller Francis Bret Harte. Geoffrey was assistant director of VVS and the architect of its ambitious history department. He looked a bit like the king in the Wizard of Id, and he had passion for his craft. We called him "Paraoh." His program started in the 9th Grade with Classical Civilization, with Geoffrey Bibby as the text. That was history straight up. In the senior year, after two of medieval and modern European history was an elective, Otigins of Western Civilization, which repeated Classical Civilization, this time with an emphasis on philosophy. It was tough.

Old Pharaoh had a large cabinet of beautiful black and white photos of ancient architecture professionally mounted on grey poster board. He would remove one to show us as Carter might have lifted a treasure from the tomb of Tutenkhamun for first public view. My term paper for the first year was an analysis of the proportional illusions of the Parthenon.

In an evening activity of draftsmanship, we all did the same multicolor Kohinoor pen realization of a protracted circle that produced the Golden Section which Bartok and artists across centuries have used as a proportional device.

And then there were students themselves. Many of us are still friends. The school had permitted me to skip a grade to get in, and, immature, not uncommonly brilliant with zero study habits, I now faced competitors who had been brought up on the east coast where primary and secondary academics were much more rigorous, additionally from at least a dozen kids whose parents were university professors. I was one of those, to be sure, but my father was a remote hero, not an on the ground guide. Classmate Phil Dempster was the son of the chairman of the U. C. B. genetics department, Henry Vaux the son of U. C. B.'s forestry school dean. Two were children of Columbia professors, and one of them, the late Kellner Schwartz, tragically lost several years later to a boating accident in Canada, was the son of Columbia's R, Plato Schwartz. Kellner may have been a genius. He certainly took best advantage of his privileged station, bought every new soft cover in sight just at the point where large soft covers were revolutionizing publishing. His dorm room was across from mine. I would go in, look at the books. Try six different works of Samuel Beckett. He was 16.

I was very challenged by this examplo, and I have books on my shelf today that I bought when wanting to catch up to him. I had only read one novel by then, The White Tower by Ullman, which I read with the Bruch Violin Concerto on my turntable. That was where I was. Varèse was not yet at the head of the line of my influences. I learned recently that several years before I arrived, Geoffrey Bret Harte had read aloud to students in an evening activity the entirety of The White Tower, then a sensation, now dated. Kellner was indeed exceptional. Poet Susan Marshall North was another. She introduced me to the Beat poets, gave me books of them, a Grove Press recording of many of them reading, including Ginsberg reading Howl. That too was music education that shaped me. I was chasing just departed busses in all directions. My beginning studies Germany led me to upper division work at U. C. Berkeley, soon after to graduate school in 1966 at U. C. Davis. One professor from the Hamburg Conservatory must be mentioned, American expatriate pianist Robert Henry, a tudent of Eduard Erdmann who assumed his position at Hamburg when Erdmann died. This man is a great artist, and he taught me the fundamentals of advance piano technique that I have never renounced. Only David Tudor has had as much influence on me, and that influence not on piano playing - I mean really now - but on general music philosophy.

U. C. Davis at that time had a rich endowment for visiting professors, so in my three years there I had for teachers Stockhausen, David Tudor, Charles Rosen for analysis, and in the final year, 1969, John Cage.

Kalheinz came first. His first assignment to the composition seminar was a design problem that Paul Klee had long ago to Bauhaus art students.

Klee set forth eight groups of lines and dots that represented high level events. For example, he would draw an icon that had three horizontal lines that started in three different places and then stopped at the same time. This represented three events start at different times and end together. Then he reversed the pattern. Then three lines that started and ended at the same time, representing three different events that started and ended at the same time. And so on.

Karlheinz asked us to write piece that demonstrated these shapes, that continued with variations in their order and interaction. That was the assignment, and we had three weeks to do it at home. But first we had one afternoon to do it in the class. My ear was not acute enough to model atonally and drop pitches onto to staves whose interval relationships i precisely heard. I always composed from the piano. But I had natural instinct for proportion, that honed by training just traced.

So I faked my way through the in class assignment, coming up with a page that looked as avant garde as all get out, although I hadn't a clear sense of what it sounded like. I thought, "I hope I survive this," turned in my masterpiece.

Stockhausen reviewed that muct the following week. He came to mine last, looked out, said, "I can't understand Dinwiddie's pitch work, but he has the best proportions in the class."

I thought, "He's good. I'm still in the game."

Three weeks later we all turned in our grander efforts, and house pianist Marvin Tartak was given the scores of all. He played them to the seminar the following week. But beforehand he came to me, said kindly enough that there were some nice sounds in the work but that he couldn't understand some on my notation, that I would have to play my piece myself.

There was a difficult section, an explosion of fireworks notes that climaxed this five minute character piece. I had the noon hour to learn it. I was at best an average pianist, inexperienced as well in public performance let along this. It was scary.

I was again last. I sat down, got a grip, went to work. The first part was easy. But that big sweep was waiting, and when I got to it, I simply faked it. I then finished with one of the best endings I have ever put onto a piece.

Stockhausen sat there with his forehead in his hand, a common listening posture for him. Then he looked at me and said, "Play it again."

I had faked the hard part, and now I was told to play it again. I played it again. And I faked the hard part again, and as closely to the way I faked it the first time as I could. Maybe half of the real notes were there both times.

Stockhausen sat there as before, looked up at me straight in the eye again, then said words that fell upon me ears like gold nuggets, "What can I say? I can't teach you anything. You know it all. You have made the first step like a lion."

Well, I didn't. But up to that point I had never had an ally at either campus of the University of California. Now suddenly I had one, and what an ally! But he turned out to be a very dangerous one. As were Tudor and Cage to be. The conservatives on the resident faculty were happy to catch the borrow light of their fame, but woe betide the students who learned anything from them, worse, admired them.

Yes, my father helped. He died the night I arrived for assignment to advanced training at Ft. Devens. I am glad to give him this credit at last. Thanks, dad.

ASTRONAUTA - In the early 60s you moved to Luebeck, Germany. What did this move change you musical interests, and musical learning?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - Luebeck was to me a second birth. All of us who were stationed there never got over it. There is a military group of the surviving of us from the 330 who were there about 50 at a time over a decade or so from 1955 to 1965. The Luebeck Association still has national reunions every four years, and four of those reunions at least have been a return to Luebeck herself. For many, it was a lifetime high point.

It was in Luebeck that i decided that I wanted to study music as a potential career. Composition certainly in mind, piano as well, but at first just to start and to follow my nose. That decision was made the first year that I was stationed there, when I was 20 years old, young, yes, but ancient for any such decision. I had already continued digging ever deeper into Bartok and modern music. Stravinsky's Agon had made a deep impression on me in the library at Ft. Jackson. Now I was in Luebeck where music and art history had been made again and again, the home of Heinrich and Thomas Mann. Organs played upon by Bach, Buxtehude, and Distler were intact in two churches while destroyed in three others, hastily rebuilt in two of those. The Totentanz Organ in the Marienkirche was replaced when I arrived, but Walter Kraft did not like the result and had it redone. Kraft restored Buxtehude's half hour free Thursday night organ concert, the "Abendmusik" that had continued uninterrupted until the Nazi era.

As a border town that barely escaped being split in two by the Iron Curtain, Luebeck's historical role as a trade hub for all of northern Europe was also severed, and in 1960 the city was still a long way from recovery from the 1942 RAF air raid that had destroyed a fifth of the old city in less than three hours.

Yet Luebeck in 1960 had a municipal orchestra under the direction of young Christoph von Dohnanyi doubled as the opera orchestra. My first date with my wife was Strauss's Salome, with Antje Silja in the title role. She was too much for Dohnanyi, who married her. Bertold Brecht's assistant in his theater in East Berlin defected and first landed here. We attended his powerful Mutter Courage. Later, when we returned to UCB, he was there again ahead of us, now directing for the San Francisco Actors' Workshop. The River Boat, a night club on the Obertrave, hosted outstanding jazz from all over the Baltic. We G.I.'s were surprised to discover that young European jazz musicians were often as good as some of our best, and with a distinctive flavor different than ours. They were not aping American models at all.

Luebeck had been at the beginning of the 20th century a center for many of the artists of Die Bruecke, including Nolde, Kirchner, Feininger, Marc, and Munch. An orchestra or opera ticket cost a couple of marks. The exchange rate was 4 marks to the dollar. We who were all enlisted men, with ranks ho higher that Sergeant, with two unfortunate commissioned officers to manage us. It was suspected that some of them were dumped in Luebeck, because they were unwanted anywhere else.

![]() |

| The "Jerkhaus" today. |

We lived in two fine houses in expensive neighborhoods, because we were too few in number to justify the construction of barracks. But all elisted men are entitled to an enlisted men's club, so one of the houses had a complete bar installed. It was hoped that it might keep us out of trouble in town, especially keep us out of Clemenstrasse, the legal red light district. That tactic did little more than add to the fun for some of us. The larger house with that bar was on Juergenwullenweberstrasse, which we shortened to Jerkhaus. Animal House would have fit. It had been inherited from the Nazis. Its back lawn descended to a boat pier on the Wakenitz river. The view straight across the river to the old city island and straight up to the Marienkirche.

Jerkhaus was next to a church. And because we alternated on shifts, there was always a third of us ready to party. Rasmussen was one who spoke German fluently, and with enough drinks good do a fine imitation of Hitler. Sometimes he would let fly with the front door open as Sunday morning Church goers passed by. Enough complaints registered with Burgermeister, and we were finally removed to a more isolated site. But it was fun while it lasted.

We were in fact, one off the cushiest duty stations in Europe. On duty we were top notch at our not ever to be discussed jobs. Off duty, Animal House was an apt description. One language translator with a particularly mean disposition upon leaving at the end of his tour duty turned to me and snarled happily, "well, I hope I did my part to start WWIII." The Cuban missile crisis was a year ahead. This was no joke. We did in fact tread very lightly off duty in matters political. That kept us out of fights most of the time.

There were many Luebecks on that magic island one mile long, 3/4 mile wide, 100 feet high, and 900 years old. Each of us took Luebeck of his choice. All remember it as occupied paradise. It was in the British Zone and it highly restricted 5 k zone that ran the length of the Iron Curtain. Only the highest security clearance would gain you admittance, plus extra vetting. It was really an honor even to be there. We were not bothered by too many of our kind. A chaplain with the rank of Major, visiting us from Baumholder, a huge infantry base in the American Zone, furious at our refusal to kiss his ass, shouted at us in the insane compulsory monthly character guidance meeting, he asked us, "Who said the Gilden Rule?" Not one of us raised a hand. He was a huge red head, and his face now matched his hais. "You know what the infantry down in Baumholder call you men, DO YOU? THEY CALL YOU THE FAIRY BRIGADE!" We grinned an evil fairy brigade grin. We were Banana Troop, Company B, 69th USASA USAREUR Brigade, 5th Army. We called ourselves "the fighting 69ers." That was not widely appreciated.

![]() |

"Air raid destroyed Dom brick Gothic area, taken when

I was 20 in 1960. This area was off limits and dangerous to enter."

John Diwiddie (this is picture AF 010, mentioned in one photo

at the end of this post.) |

One of those first concerts that I first attended was in the partially restored of the DOM, the oldest of the Luebeck churches, one of two towers, the other the Marienkirche a half mile away, and it once had the rank of "cathedral.", started by Henry the Lion in the late 12 century. The DOM had a brick Gothic addition at the opposite end which had been down to its dome ribs. When I first arrived, I broke into this off limits area and photographed what I saw. The domes were shattered to the ribs, some of those broken as well. On them, small bushed grew from the nourishment of the broken bricks and mortar. On the ground, tall wet grass come up to my knees. Limestone sarcophagus covers carved with images of bishops were scattered about, titled at odd angled like huge drunken tombstones. They had been a part of the destroyed chamber's floor and had probably been blown up and dropped back by the shock waves of blockbusters that preceded incendiaries, the standard carpet bomb cocktail that bomber Harris was trying out on Luebeck before going after Hamburg the following year. If one of those had hit the DOM directly, the DOM would have been flattened. What else might have done this? Perhaps the incendiaries that did hit directly also had substantial shock waves.

Click click click went my camera. The images still frighten me. I am sending copies to the DOM archivist this spring.

The concert in question was Mozart's C minor Mass. The orchestra and chorus was installed in a temporary rustic wooden loft in sturdier Romanesque nave. Still, the roof had burned and was now covered with tin. It was the slowest performance of Mozart's greatest choral work that I was ever to hear, but it was musical. Imagine hearing this work for the first time in a setting like that. imagine! Another life changing discovery for me.

Our city orchestra conductor was Christoph von Dohnanyi, just getting started. One night he played Bartok's Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta, and of course we had to go. Bartok anything, and I was off. I was by now Bartok's greatest fan. I glanced at the rest of the program. The first symphony of Shostakovich. The Petite Symphonie Concertante for Harpsichord, Piano, Harp, and Orchestra by Frank Martin. Frank Martin. An American perhaps?

The Shostakovich floored me. Then came the Martin and although I have issued with it now, in that concert it too floored me. I left the concert knowing that I would perhaps never again hear an orchestral concert so memorable. Shostakovich's symphony was premiered when he was 19. I was 20. And i wanted to become a composer! It was impossible to ignore that absurd contrast.

There was the literary tradition, centered on Heinrich and Thomas Mann. You could read Buddenbrooks and walk the streets to trace its story. You could follow the trail to the posh resort and casino town, Travemuende, where Tonie's chances of a happy marriage were broken by family intrigue that prevented her from marrying outside of her class. You could follow the footsteps of Tonio Kroeger and his star crossed friendship. Buddenbrooks was full of music. You could retrace it too, right up to the organ lofts of the Marienkirche that was across the street from Buddenbrookshaus. It is a museum today.

![]() |

"Three statues by Ernst Barlach on the front façade of the

Katherinium, a deconsecrated Catholic church now also

a museum. The middle statue is one of the most famous works

of modern sculture in Germany."

John Diwiddie. |

And the great sculptor, Ernst Barlach, who for me seemed to carve into statues of peasants and beggars what Bartok wrote into his music. Bartok refused ever to speak German again when the Nazis came to power. Yet here in Luebeck I saw Bartok and Barlach in each other. So, thats is a bit of what Luebeck did to me, why to this day it is my second home. In the past 10 years I have spent more time in Luebeck by far than in Berkeley, now 65 miles south of us. The military supported off duty education, so I took modal counterpoint and beginning harmony at the Musikakademie. That is how I started..

ASTRONAUTA - In 1963 you attended a concert at the San Francisco Tape Music Center, at 321 Divisadero Street, San Francisco, CA, and it was the first time that you saw John Cage and David Tudor in person. What are your memories from that event? Was that your first personal contact with the SFTMC group? Did you keep in contact with them (Ramon Sender, Pauline Oliveros, Morton Subotnick, and Bill Maginnis) after that event?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - I was 23, just back from Germany. In Luebeck I had discussed John Cage with my theory teacher Jens Rohwer, a conservative-modern composer who respected Cage, even though he considered him more philosopher than composer. In an conversation with Henry Cowell at Amerikahaus in Hamburg in 1962, we discussed Cage, but Cowell was oddly unfamiliar in speaking of him, always calling him by his full name. I felt that Cowell had issues with Cage, that perhaps Cage had gone too far for him beginning with Silence, but I did not pry. I did wonder.

And that was all that I knew until the Divisadero Street concerto about John Cage.

So when four of us, the other two Malcolm and Linda Genet, whom I had known at Tulane who were also friends of Ian Underwood who was performing this night, went to this show, it was a new experience for all of us. Linda now ran the ASUC Art Studio, and Malcolm was a grand student in the UC English Department. All of us had prior experience in theater of the absurd and experimental theater at Tulane. Malcolm and I were two of the only members of TUT, the Tulane acting troupe, aho were not drama majors. Malcolm had played Etaoin Shrdlu in Rice's The Adding Machine. I had been the unblinking bell boy in Sartre's No Exit. I had been Thyrsis in Millay's Aria da Capo when a freshman at VVS. At Ft. Devens, I attended the Harvard Adams House world premiere of then student Arthur Kopit's Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama's Hung You In The Closet, And I'm Feelin' So Sad. We had seen Waiting For Godot in New Orleans' famous Theater of the Vieux Carre. We were old pros, ready for anything that silly old new music had to throw at us. So we thought. Winter Music and Cartridge Music were on the program that evening. At one point Iam Underwood sat down at a grand piano and played the opening parallel sixth passage in Brahms's D minor Piano Concerto. Then he got up, walked robotically over to a Sousaphone, stuck his head into its bell.

Who can remember too many details of this sort? Everything ephemeral by design. Nothing carrying forward. In all the plays cited, things do carry forward, if in the case of the Beckett on a Moebius strip. Cage was there, and I saw him on stage from time to time, David was there, but as always he was listed as an assistant. We didn't have a clue hat we were in the presence of one of most extreme musical geniuses alive. Some called him the greatest living pianist. I once asked David how long it took him to learn an average Beethoven Sonata. He just told me that he had quit piano because it was too much trouble. He answered, "4 hours." Then we didn't even know that he was a pianist.

We went home laughing ourselves silly. We knew what Dada was, but we had never before met it unleashed a theater.

As we approached the tunnel through Yerba Buena, I blusted, "I can't take John Cage seriously; he's too funny." The words stuck to their stupidity. Why must what is ridiculous not be serious? After all, the world situation is pretty ridiculous and it is very serious.

The first time I actually met John Cage was in 1968, at Mills College. I had already taken David Tudor's course and knew much more about him that I did when I was 23. But I was still very much the composer with a composer's buttoned down ideas about what a composition should be. I was ready to accept anything except one thing, a composition with declared rules that it then failed to follow. That I was not ready to tolerate.

Only one work was played that night, by David Tudor in fact, Reunion, written for John Cage and Marcel Duchamp, its performers. The performance was a game of chess played upon a board conceived by David and built by Lowell Cross. Each of 64 positions had a pinhole. The board itself was the top os a box. Inside under each pin hole was a photoelectric gate that would switch depending on whether or not it was covered by a chess piece.

64 leads from these gates radiated to mixers and synthesizers, whatever, then to the four Altec theater speakers that were the Easter Island totems of the famous Julia Morgan designed theater.

The two masters sat on a platform, and as usual, with the lights dimmed, that theater where the previous year Milhaud had to introduce Stockhausen and was not entirely happy about it, was spooky and dark. I watched intently and listened to hear what I thought should be exciting changes in the sounds coming out of the speakers.

What was coming out of the speakers sounded to me instead like anonymous default electronic music hellzapoppin. By the time the show was over, I was convinced that something had gone wrong, so I marched back stage with my tidy scruples, addressed John cage, "Mr. Cage..." I even had a tie on. I told him what I had NOT heard, and I asked him what was going on.

He laughed, retorted, "Oh, the chess board didn't work so we faked the whole show!" It was battle time, and if I made an ass of myself, I don't think that I bored him. He soon shouted at me, "BEETHOVEN IS TOILET PAPER."

We were however destined for rich friendship, and he was in corner more often than he ever had to be, stories for another time. But I do have a follow up on this one. When he was at U.C. Davis in 1969, I was a kind of gofer, occasional assistant. One night we stayed up all night together talking and getting pretty ripped. It was for me an unforgettable night, and like another such night that I spent soldering contact mikes with David Tudor, I took full advantage to ask shameless questions.

I reminded him of our first encounter, but i was out to prove to him that since then I was wiser and less uptight young man. I spouted some nonsense about understanding now that he was not so much slamming Beethoven that night as elevating toilet paper to a place of respect, a Zazen sort of thing. Just idiotic of me. John laughed tolerantly; "The truth is that I had had several margaritas."

ASTRONAUTA - What are your memories from meeting Karlheinz Stockhausen?

JOHN DINWIDDIE - Karlheinz never toed the line. He was contracted to be on deck in September. He was finishing Telemusik in Japan, so he arrived a month later, leaving Larry Austin to preside over the first month, which Larry did very well indeed, another story. When Karlheinz finally did arrive, he brusquely entered the seminar room. Inside was a conference table that was almost too big for it, and one end was close to the door from the hallway. I was seated at that end of the table, so when Karlheinz barged in, he all but knocked me out of my chair. Everyone in the room jumped up. It was if a general had entered a roomful of startled but eager cadets. I was pinned between the table and the door, which kept me seated. I thought, "Uh on!" I was a past master of bad beginnings.

Roll Call: who for the record was there?

From Germany

Rolf Gelhaar

From Brown University

Gerald Shapiro

From UCB

Will Johnson

Jonathan Kramer

Alden Jenks

From UCD

Stanley Lunetta

Dary John Mizelle

Me

Undergrad UCD auditors

John Moore

Julian Woodruff (who was to distinguish himself later in Charles Rosen's analysis seminar, also to write a fine improvisational format, Subjects of the Sun.)

Mark Riener

That was the class, and for me the court jester was the brilliant and notoriously irreverent Stanley Lunetta, one of the cofounders of Source Magazine and one of Larry Austin's protégés, the other Dary John Mizelle.

I have never in my life met a person who made a more stunning first impression than Stockhausen. He was 38 years old in 1966 at the final summit of youth. He was aristocratically handsome, and he radiated intelligence. His high baritone voice seduced immediately. He designed his own clothes. He wore a reversible Harris tweed cloak that he had designed and had tailored in japan. He was Beau Brummel come back from the dead. Perhaps Liszt. Wagner maybe?

![]() |

"Stan Lunetta and I, Gerda's guitar, on the cat walk above

the shielding of the U.C.D. cyclotron where David Tudor

staged Ichiyanagi's Distances and Larry Austin

rounded out the show by writing an improvisational

format for the whole building, calling it "Cyclotron Stew."

The directions for the Ichiyanagi are to play anything

you wish as long as you are 30 feet away from

your instrument(s).

We were not, but we were far enough for the concept

to work as intended. Larry's piece turned down the lights

to spook the audience which was seated on folding chairs

atop the massive shielding. The shield door opened,

then closed, sending a bouncy shock wave through

the audience a la William Castle. A fork with its blinking

yellow light drove around, and the light threw up to

the walls atomic ghosts. The warning siren went on and off.

That and whatever else could be operated without

setting off a chain reactions was

Cyclotron Stew."

John Dinwiddie

Photo: David Freund, SOURCE, Issue 3. |

Stan Lunetta had none of it. Stan worshipped Stan Lee and Spiderman comic books and little else besides his family. Stan had built in Brechtian distance switch. One day two weeks after Karlheinz arrived, Stan looked down under the conference table, popped back up and reported on what he saw: "Hey, everybody, everybody in here is wearing Karlheinz Stockhausen shoes except me and John Dinwiddie!"

In the winter trimester, when David Tudor was also a visiting professor, we gave a concert at Herz Hall, U. C. B. Kontakte, Klavierstuck XI, and Zyklus were on the program, plus a choral work by Franco Evangelisti. Stan was the percussionist, David, gamely complying with his contract, the pianist.

The concert went very well, and at the end we did what had become ritual to us in David's live electronic music seminar, which was simply to pack up and get out of the place. There was a routine for winding long cables, criss crossing them around wrist and back arm, so that they could be thrown across a stage in the next concert without tangling. This was ritual. We were all but a priesthood.

Karlheinz watched us from the empty orchestra rows. He came from the European tradition where composers did not wind up cables. Stage hands did. He must have felt the isolation there, where there were no stage hands, stood up, said "I will help." For him it may have been a sea change.

As he was working, a lone hippy entered the empty hall, came down an aisle and approached him, called out "Hey, man, do you smoke dope before you write your stuff?" Karlheinz was indignant. "I never smoke dope."

The hippy turned back, clearly disappointed. After a few rows however he turned around again. "Hey, man, do you smoke dope WHILE you write your stuff?" More indignant: "No, I just told you. I never smoke dope."